Posts Tagged ‘Lena Shull Book Contest’

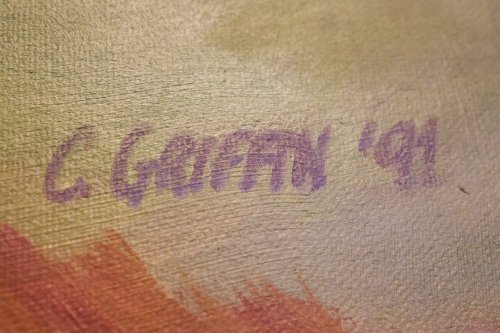

Brush Strokes

Posted in Art, family, Imagery, poetry, tagged Bill Griffin, Ekphrastic poetry, Gail Peck, imagery, Impressionism, Lena Shull Book Contest, Main Street Rag Publishing, NC Poetry Society, NC Poets, poetry, Southern writing, The Braided Light on February 14, 2025| 5 Comments »

Ephemeral

Posted in family, Imagery, Photography, poetry, tagged Ana Pugatch, Bill Griffin, Engrams, family, Lena Shull Book Contest, nature photography, NC Poetry Society, NC Poets, NCPS, poetry, Redhawk Publications, Seven Years in Asia, Southern writing on January 12, 2024| 6 Comments »

Bunnies for Themselves – Becky Gould Gibson

Posted in Ecopoetry, Imagery, Photography, poetry, tagged Becky Gould Gibson, Bill Griffin, death, ecology, Ecopoetry, imagery, Lena Shull, Lena Shull Book Contest, nature, nature poetry, NC Poetry Society, NC Poets, NCPS, PCNC, poetry, Poetry Council of North Carolina, Southern writing on May 28, 2021| 5 Comments »

[with 3 poems by Becky Gould Gibson]

Amelia’s Papa Jimmy brought the bunnies to playschool yesterday. Four of them had fallen from a nest destroyed as he cleared a field two weeks ago. No mother in sight.

When we heard he’d bought bunny milk at Tractor Supply and was feeding them four drops every two hours we first thought, Is he raising them for the dogs? Not to eat, to teach. He trains young beagles to hunt; maybe they need to learn the smell of rabbits?

But no, not at all, it’s just that Jimmy can’t leave helpless young to die. Tractor Supply will mix up formula for any small critter you may have need of. He used a dropper until they learned to suck from a nipple. Two weeks later they’re hopping, eating tasty greens.

Yesterday each four- and five-year old got to hear the bunnies’ story, touch their soft ears and heads. Today Jimmy will release them at the edge of the woods, restored to bunny-ness, preserved for no other purpose than themselves.

. . . . . . .

Stand of Birches

The woods are wet this morning – rain yesterday

or the day before, maybe – such a sense of quiet,

all the damp peace of it, mostly trees to be with,

birches especially, minimalists in chic black and white,

raw silk with horizontal markings like wounds

slashed across white paper, dashes, staples, lines

of ghostly scansion, every beat, every syllable

of wood and glade accented, no scales or hierarchies

scored in their bark, rather universal emphasis,

as if everything mattered – this tiny white-headed

flower, this ant on some errand, even the mosquito

buzzing my ankles, these low-growing grasses,

branch with its bark pulled back, underbelly softening,

chartreuse mosses – though brief, briefly important.

. . . . . . .

These poems by Becky Gould Gibson are from her book Heading Home, the winner of the inaugural Lena Shull Book Contest in 2013. The poetry is strongly rooted in family and place but also richly steeped in literary tradition and history. I keep coming back to Stand of Birches for its eloquent, even spiritual expression of the deepest premise of Ecology: not utilitarian, not exploitative, not derivative or charismatic or anthropocentric – each living thing in all its interconnectedness is of value in and for itself.

Yes, yes, OK, OK, even mosquitoes.

In 2012 the Poetry Council of North Carolina elected to dissolve its organization and merge its residual funds with the North Carolina Poetry Society. Since 1949 PCNC had promoted the craft of poetry in the state with its annual contests; now in collaboration with NCPS it established an endowment to sponsor the annual Lena Shull Book Contest for an unpublished full length manuscript by a North Carolina writer, named for founder and first president of PCNC. Becky Gould Gibson was the first Lena Shull winner.

. . . . . . .

Scuppernongs

+++ Immortal life will be given . . .

+++ The Lord of harvest gathers us, / Sheaves of the dead –

++++++++++++++++++++++ for Bill

When death lifts its edge a little,

as in the first movement of Mahler’s C minor symphony,

you wonder will you be ready.

We finish a bowl of scuppernongs from the market,

wild bronze from childhood,

delighting in the bite, thick skin between our teeth,

touch tongue-tip to tongue-tip.

You taught my tongue to talk back.

I recall all those summers,

you in another county, nearly a decade before we would meet.

Now, come with me.

We’re together, then. It’s a languid afternoon in late August.

I’m eight. You’re ten.

As for death, I still think I can talk my way out of it.

Follow me across the un-mowed yard,

weeds tickling our legs,

to the scuppernong bush at the edge of Mr. Marcus’s field.

For you, death is no fiction.

At six, made to duck under your desk at school,

wear a dog tag, so someone could identify your body.

No bucket. We stuff ourselves madly.

Know what happens if you swallow a seed? We laugh.

No, love. It is not my own death I worry about, but yours –

will I ever be ready for it?

To be alone as I was that distant August,

memory plucking the fruit of you, scuppernong ripe in my mouth.

Becky Gould Gibson

. . . . . . .

Lines to Yeats on the Anniversary of His Death

++++ January 28, 1939

++++ for Alice

To a soul just fledged, still damp, in a nest

Of paper, flimsy bits of Plato, Paul,

Shelley, Wordsworth, Tennyson, all the rest

Who believed (or even half-believed) soul

Could soar above the earth (earth a mere cast

Of heaven), spirit somehow separable

From flesh, you came, William (my dear Willie)

With your poems of pure song, heart’s own music.

No wonder it entered my veins, my pulse

Learned to tick your rhythms. No matter you

Warned not to pleasure soul at the expense

Of body, who could even listen to

Such warning with such a beat, sound and sense

So perfectly married, as if to show

A manmade thing could become immortal,

Gold bird on a gold limb sing out its soul.

You made me more impatient than ever

To conceive such a poem of my own.

Your artless art merely fed the fever,

Yet every line fell stillborn from my pen.

Blood had become a colorless liquor

Nourished on symbols. Life had to happen,

And it did. Not a woman but a child,

Rather a child’s birth. It was a girl-child

Split me apart. No way to staunch the flood

(Nothing’s sole or whole that has not been rent)

Of blunt necessity. You had your Maud.

I had my Alice. She caught me up, lent

Me her knowledge. She, no man or bird-god,

Made loins shudder, roused me from those years spent

In abstraction, taught me bone, bowel, breath,

Body’s mortal work. She taught me my death.

Becky Gould Gibson

three poems from Heading Home, Winner of the 2013 Lena Shull Book Contest, Main Street Rag Publishing Company, © 2014 Becky Gould Gibson

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

Very true. And not that she ignores the grief and woe of living but somehow makes all of life a…