Posts Tagged ‘Southern Appalachians’

Deep Time

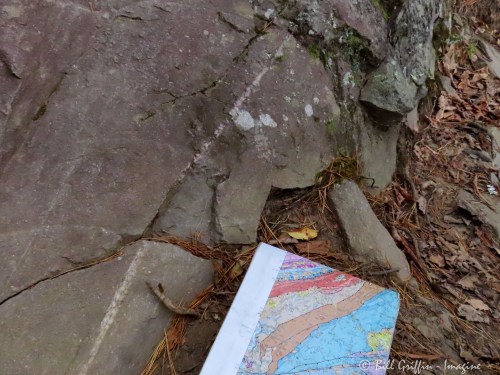

Posted in ecology, Ecopoetry, Imagery, Photography, tagged Bill Griffin, Ecopoetry, Emilie Lygren, Geology, Great Smoky Mountains Institute at Tremont, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, imagery, Janet Loxley Lewis, nature, nature photography, nature poetry, poetry, Robert Wrigley, Southern Appalachian Naturalist Certification Program, Southern Appalachians on November 15, 2024| 5 Comments »

Community

Posted in Imagery, tagged Bill Griffin, community, ecology, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, imagery, lichen, nature, nature photography, NC Poets, poetry, Redhawk Publications, Scott Owens, Sky Full of Stars and Dreaming, Southern Appalachians, Southern writing on March 11, 2022| 12 Comments »

[with 3 poems by Scott Owens]

Which came first? Separate a few of the living creatures in the photo above and see what you can identify: the distinctive mottled leaf of Saxifrage; beneath it a glimpse of moss, its diminutive creeping green; a big hairy leaf, I should know that one but I don’t. Down in the damp there’s bound to be a little township of bacteria, waterbears, wormy things, arthropods.

And what’s that right in the center? A little stemmed goblet corroded like verdigris growing out of that patch of gray-green flakes (squamules)? Center stage – lichen, probably Cladonia pyxidata. Its tiny cup is pebbled within by extra lichen bits growing there (more squamules!) and some of the rough and powdery appearance may be an obligate lichen-loving fungus taken up residence. So which came first in this little community of many kingdoms and phyla?

Most likely the lichen comes first. It can hold onto bare rock where nothing else lives. It gathers moisture into itself out of the very air and how could a wandering moss spore resist? Anything drifting by may land and latch. Plus that little lichen chemical factory can break down rock so that others may use the minerals. Pretty soon a Saxifrage seed finds just enough earth to sprout and enough wet to grow and wedge its roots further into rock (saxifrage = rock-breaker). Everything discovers what they need; everyone adds to the life of the community.

What gifts may I add to my little community? A bit of cautious optimism and encouragement. An appreciation for all living things (OK, yes, that does extend to human beings, at least I’m trying my best). Appreciation of a good joke and appreciation as well of the folks who tell bad jokes. Curiosity and a sense of wonder. The world’s best recipe for Nutty Fingers.

We all need something but we all bring something. Who knows, maybe what I’ve got is just what you need. When one really gets down to it, all the stuff growing in that photo looks pretty haphazard and messy. Just like a real community. Just like life.

And if you know what that hairy leaf is, please tell me!

. . . . . . .

In the Cathedral of Fallen Trees

Each time he thinks something special

will happen, he’ll see the sky resting

on bent backs of trees, he’ll find

the wind hiding in hands of leaves,

he’ll read some secret love scratched

in the skin of a tree just fallen.

Because he found that trees were not

forever, that even trees he knew

grew recklessly towards falling,

he gave in to the wisteria’s plan

to glorify the dead. He sat down

beneath the arches of limbs reaching

over him, felt the light spread

through stained glass windows of leaves,

saw every stump as a silent altar,

each branch a pulpit’s tongue.

He did not expect the hawk to be here.

He had no design to find the meaning

of wild ginger, to see leaves soaked

with slime trails of things just past.

He thought only to listen

to the persistent breathing of tres,

to quiet whispers of leaves in wind,

secrets written in storied rings.

Each time he thinks something special

will happen. He returns with a handful

of dirt, a stone shaped like a bowl,

a small tree once rootbound against a larger.

Scott Owens

from Sky Full of Stars and Dreaming, Red Hawk Publications, © 2021

. . . . . . .

I’ve admired Scott Owens for many years, not only as a poet but even more so as a builder of community. Scott’s writing wields its openness, its wonder, its unflinching honesty to invite us to realize we are all part of one human family. As in his poem, Words and What They Say: the hope we have / grows stronger / when we can put it into words. Not only words – in everything else he does Scott is building as well. He teaches, he mentors, he makes opportunities happen for the people around him. Perhaps his poems are a window into why he values people as he does, and why he works so hard to make hope a reality.

Sky Full of Stars and Dreaming is Scott Owens’s sixteenth poetry collection. He is Professor of Poetry at Lenoir Rhyne University, former editor of Wild Goose Poetry Review and Southern Poetry Review, and he owns and operates Taste Full Beans Coffeehouse and Gallery where he coordinates innumerable readings and open mics, including POETRY HICKORY, and enlarges the community of creativity.

. . . . . . .

The Possibility of Substance Beyond Reflection

I didn’t see the V of geese fly overhead in the slate gray sky as I sat waiting for a reading in my Prius in front of the Royal Bean Coffee House & Gift Shop in Raleigh, NC.

What I saw was the V of geese presumably flying overhead in the slate gray sky reflected in the slate gray hood of the Honda CRV parked before me in front of the Royal Bean Coffee House & Gift Shop in Raleigh, NC.

And they took a long time to travel such a short distance, up one quarter panel, across one contoured crease, then the broad canvas of the hood’s main body, down the other crease and onto the edge of the opposite quarter panel before

disappearing into the unreflective nothingness beyond, where even they had to question just how real they were or just how real they might have been.

Scott Owens

from Sky Full of Stars and Dreaming, Red Hawk Publications, © 2021

. . . . . . .

Sharing a Drink on My 55th Birthday

Sharing a drink on my 55th birthday,

my son, his tongue firmly planted

in his cheek, asks what advice I have

for those not yet as old as I,

and I, having had too much to drink,

miss his humor and tell him

always get up at 5

as if you don’t want to miss

any part of any day you can manage.

Clean up your own mess

and don’t clean up after those who won’t.

Take the long way home,

hoping to see something new,

or something you don’t

want to not see again.

Stay up late, drink in as much

of every day as you can.

Be drunk on life, on love, on trees,

on mountains, on spring,

on rivers that go the way

they know to go,

on words, on art, on dancing,

on poetry, on the newborn

fighting against nonexistence,

on night skies, on dreams, on mere minutes,

on the ocean that stretches beyond

what you ever imagined forever could be.

And when someone asks you

what advice you have, give them,

as you’ve given everyone and everything,

the best of what you have.

Scott Owens

from Sky Full of Stars and Dreaming, Red Hawk Publications, © 2021

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

*** Extra Geek Credit — the lichen Cladonia pyxidata is host to the lichenicolous (lives on lichens) fungus Lichenoconium pyxidatae. Such fungi are parasites of their lichen host and mostly specific to a single genus or even to single species of lichen, but although some may be pathogens for the lichen in many cases the relationship is commensal. No harm done. Join the party!

![[#Beginning of Shooting Data Section]<br /> Nikon CoolPix2500<br /> 0000/00/00 00:00:00<br /> JPEG (8-bit) Normal<br /> Image Size: 1600 x 1200<br /> Color<br /> ConverterLens: None<br /> Focal Length: 5.6mm<br /> Exposure Mode: Programmed Auto<br /> Metering Mode: Multi-Pattern<br /> 1/558.9 sec - f/4.5<br /> Exposure Comp.: 0 EV<br /> Sensitivity: Auto<br /> White Balance: Auto<br /> AF Mode: AF-S<br /> Tone Comp: Auto<br /> Flash Sync Mode: Front Curtain<br /> Electric Zoom Ratio: 1.00<br /> Saturation comp: 0<br /> Sharpening: Auto<br /> Noise Reduction: OFF<br /> [#End of Shooting Data Section]](https://griffinpoetry.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/dscn0524.jpg?w=500)

Very true. And not that she ignores the grief and woe of living but somehow makes all of life a…