Posts Tagged ‘Southern Appalachian Naturalist Certification Program’

Deep Time

Posted in ecology, Ecopoetry, Imagery, Photography, tagged Bill Griffin, Ecopoetry, Emilie Lygren, Geology, Great Smoky Mountains Institute at Tremont, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, imagery, Janet Loxley Lewis, nature, nature photography, nature poetry, poetry, Robert Wrigley, Southern Appalachian Naturalist Certification Program, Southern Appalachians on November 15, 2024| 5 Comments »

Becoming Something New

Posted in Ecopoetry, Imagery, Photography, poetry, tagged Anne McCrary Sullivan, Bill Griffin, Ecopoetry, Great Smoky Mountains Institute at Tremont, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, GSMIT, GSMNP, imagery, John Morgan, nature, nature photography, nature poetry, poetry, Southern Appalachian Naturalist Certification Program, Southern Appalachians on March 4, 2022| 14 Comments »

[poems by Bill Griffin, John Morgan, Anne McCrary Sullivan]

Always something new. Trees I’ve passed a dozen times, these stones, did they always look like this? Oh sure, no doubt those gray-green blotches scattered here & there just so sparked some cryptic synapse of recognition: lichen. But slow down, kneel, look close and learn, understand a fragment of what is happening here and has been happening for too long to grasp. Always something new to discover.

How do they do it? Fungal hyphae, infinitely winding threads coil to embrace their chosen algae, held in their arms like waifs. Separate them, fungus and plant, separate kingdoms, and the textbook shows their single forms: flask of gray goo, flask of green. Let them mingle, though, and they create miniature cityscapes, ramparts, pastorales wilder than the dreams of Seuss.

But that fungal/algal friendship – it’s not all long-stemmed roses and dark chocolate. In school I learned lichen = symbiosis, mutual give and take, but there’s evidence of some darker biochemical power-brokerage at play. Fungus need’s sugar from algae’s photosynthesis to live (or some fungi hook up with cyanobacteria). Algae get a scaffold for stability, a moist enclave, protection from the sun. But fungus tweaks its algae to make them spill more sugar, and no algal cell is ever free to leave. Vaguely sinister.

Still the two together create a world neither could create alone. How old is it, that 7 cm patch of speckled gray on the rock face half way up Lumber Ridge, staking its stark black divide between the creeping yellow patch adjacent? How long have they been growing there? Ten years? A hundred? Nine hundred species of lichens in the Smokies (at least!) making infinitesimal advances, making spores or little baby lichen granules for the next boulder over, the next bare patch of bark – stable, solid partnerships of mycobiont/photobiont as old as stone. As everlasting and as changeable, evolving, as this gradually eroding ridge.

I will never walk this way again without wondering. Actually, I’ll never walk anywhere without lichen – between the boards on my porch, on every tree (look close!), even thriving on that old junker someone’s hauling west on US 421. I can’t help it now, noticing their different forms and colors. Their sweet pocked apothecia. Their spreading. Lichens, steadfast, pursue their wonderfully odd and ancient lifestyle and I am becoming something new.

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

Becoming Something New

+++ Lichens are a lifestyle.

+++ Dr. James Lendemer, NY Botanical Garden

Mountains stretch themselves beneath

the undifferentiated open,

overhead unblinking: ridgeback, rock face,

cove & holler to the sky

look like Chigger Thicket, Princess Shingles

cradled in arms of ageless folded earth

upholding hornbeam, hemlock, oak

yet closer each bole the shepherd

of its own beloved

flocks, foliose & fruticose,

spire cleft & spore sac all sustained

upon the nod of small green globes,

embrace of interlacing hyphae.

From two as far removed as earth and sky

comes something new.

Perhaps we shouldn’t name it love, this dance

so intimate, maybe just the way

life gets things done, gets through

with welcome damp, a speck of sun

for sustenance, enfolding arms

to lean into each other, but consider this:

can any two who persevere

in all this ancient making kingdom

ever take more than they give?

Bill Griffin – for John DiDiego and the Likin’ Lichens course of the Southern Appalachian Naturalist Certification Program, Great Smokies Institute at Tremont

Chigger Thicket – Usnea stigosa

Princes Shingles – Cladonia strepsilis

+++ Thanks to Dr. James Lendemer for the common names of lichen

+++ and for opening the door to worlds unseen . . .

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

Poetry and the National Park Service

Sometimes a poem takes me to a new place of heart and spirit, like walking through a national park takes me to a new place of earthforms and creatures. These are experiences of curiosity, wonder, awe, renewal – in the encounter I become something new.

The National Park Service is all about poetry. The National Historic Site Longfellow House – Washington’s Headquarters includes many resources from Romantic nature poetry to Emerson and transcendentalism. Other links at NPS.gov range from Mary Oliver and Ed Roberson to Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner and Arther Sze. Over the years many writers have served as poets-in-residence in various parks; poems they wrote during these times are featured online and I’m sharing two today. The Park Service recognizes the importance of poetry at the interface between human person and nature, as is in this online statement:

Unlike most Romantic nature poetry, which primarily focused on the sentimental beauty of nature, many modern nature poems examine ecological disasters or human’s role in the environment’s decline. Through poetry, these “eco-poets” explore this ever-evolving relationship between human and nature. Some poems bring awareness to ecological crises or challenge readers to reflect on their own relationship with nature. Still, some are odes of gratitude to nature or elegies for the changing environment, and others are a call to action.

National Park Service nature poetry resources

Poems by Poets-in-Residence at National Parks

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow nature poetry at NPS.GOV

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

Vision

Followed a fox toward Polychrome Pass.

Red smudged

with black along its lean rib-cage,

it rubs its muzzle on a former meal,

ignores the

impatient poet on its tail.

Then nearing the overlook, sun shearing

through low clouds

transmutes the view to glitter. Everything’s

golden, scintillant. I feel like a seedpod wafted

into space and

check my shaky hands on the steering wheel.

As the road crests over its top, boundaries

dissolve. Beside that

sheer intractable edge, I greet my radiant center,

discharge all my terms. How easy it seems

to channel between

worlds, my old self dying into a new,

with nothing firm to hold me here

but love. And that’s

what nature has it in its power to do.

John Morgan

from his poetry collection entitled The Hungers of the World: Poems from a Residency, written after a stay at Denali National Park in June, 2009.

Of his time in the park John writes, “Being in residence means, in a sense, being at home, and having the wonderful Murie Cabin to live in made me feel a part of the wilderness whenever I stepped outside. Over the course of ten days the boundary between myself and the natural world grew very thin. These intimations culminated, toward the end of my stay, with the experience recounted in the poem Vision.”

. . . . . . .

At Season’s End, Singing to The Alligator

I was prepared to arrive at the slough and for the first time

find no gators there, but there was one swimming steadily

away from the boardwalk. I watched.

I began to sing to him (I don’t know why), hum rather.

He slowed down. A coincidence probably. I kept humming.

He stopped, turned sideways, looked at me.

I came then as close to holding my breath

as one can while humming.

He began to submerge (felt safer that way, I suppose)

but did not submerge completely. I hummed.

Slowly, he swam toward me

stopped directly beneath me

hung in the water the way they do

legs dangling, listening.

(Be skeptical if you will.

I know that gator was listening.)

We stayed that way a long time,

I leaning over the rail humming,

he looking up at me, attentive—

until he folded his legs to his body,

waved that muscled tail and left me

alone, dizzy with inexplicable joy.

Anne McCrary Sullivan

from Ecology II: Throat Song from the Everglades, a book of poems inspired by her residency at Everglades National Park.

Of her art Anne writes, “Poetry is a way of seeing. It requires heightened attention to detail and a sensitivity to pattern and relationship. It looks simultaneously at inner and outer worlds, locates connections, and ultimately presents a meaning-charged kernel of experience.”

{Sounds to me like naturalist methods and poetry involve parallel attitudes and aptitudes. – Bill}

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

Lichen Welcome

Posted in Ecopoetry, Imagery, Photography, poetry, tagged Alice James Books, Bill Griffin, Ecopoetry, Great Smoky Mountains Institute at Tremont, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, GSMIT, GSMNP, imagery, Jane Mead, nature, nature photography, nature poetry, poetry, Southern Appalachian Naturalist Certification Program, Southern Appalachians, To the Wren on February 25, 2022| 6 Comments »

[with 4 poems by Jane Mead]

What is Leafy yet has no Leaves?

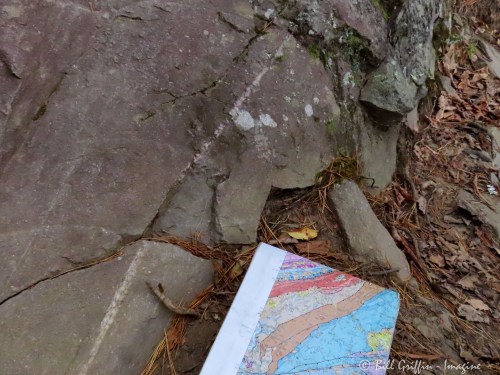

On our way home Mike and I pull over at Newfound Gap but not for the Appalachian vistas: it’s our last stop to hunt lichens before we leave the Smokies. And maybe an opportunity to spread some lichen joy.

No need to hunt – stop moving long enough and a lichen will find you. Two old guys squinting through magnifying glasses at rocks and bark, though, and it also isn’t long before a passing family asks, “What gives?” “Looking at all the lichens,” Mike answers. “What’s a lichen?” Jackpot! Mike begins to tell their story . . . “a whole little world of fungus and algae” . . . while I wander on.

Now a couple asks me why I’ve raised my camera toward this one tree among the millions. Spreading from its bark are crooked fingers, hands of crones, veined, flattened, beseeching. “That’s lichen?” says the woman when I tell her. “I thought it looked like wind had plastered leaves against the trunk.” Exactly, that’s just how it looks. But it has no leaves!

Lobaria pulmonaria: Lungwort, you need a new name. Not even remotely kin to spiderworts, toothworts, liverworts, you are no wort at all – though your presence is atmosphere’s benediction. Draw deeply, my lungs! Exhale wonder! What shall we call you, Leafy without Leaves? Troll’s Greeting? Across the Aisle? Or maybe simply Lichen Welcome.

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

Three Candles

And a Bowerbird

I do not know why

the three candles must sit

before this oval mirror,

but they must. –

I do not know much

about beauty, though

its consequences

are clearly great – even

to the animals:

to the bowerbird

who steals what is blue,

decorates, paints

his house; to the peacock

who loves the otherwise

useless tail of the peacock –

the tail we love.

The feathers we steal.

Perhaps even to the sunflowers

turning in their Fibonacci

spirals the consequences

are great, or to the mathematical

dunes with ripples

in the equation of all things

windswept. Perhaps

mostly, then, to the wind.

Perhaps mostly to the bowerbird.

I cannot say.

But I light the candles: there is

joy in it. And in the mirror

also, there is joy.

Jane Mead (1958-2019)

. . . . . . .

These poems by Jane Mead appear in To the Wren: Collected & New Poems (Alice James Books, Farmington ME, © 2019). The book spans three decades of Mead’s life: running her family’s vineyards in Napa Valley; the death of her mother; her own cancer which ultimately took her life. All through her poetry there is a fierce seeking for identity – But always it’s either I or world. / World or I. Relentlessly she seeks justice for the earth, for creatures, for the self. Poet Gerald Stern writes, “Jane Mead’s mission is to rescue—to search and rescue; and the mind, above all, does the work…. Her poems are a beautiful search for liberation and rebirth.” Nature is not something we write about; nature is what we are.

[Above poem excerpt by Jane Mead is from In Need of a World.

Three bright yellow lichens of the Smokies found at Newfound Gap:

= Xanthomendoza weberi

= Caloplaca falvovirescens, “Colonel Mustard”

= Caloplaca flavocitrina, “Continental Firecrackers”

++++ – – Species identification revised 2/28/2022 after review by Dr. Lendemer]

. . . . . . .

The Argument Against Us

The line of a man’s neck, bent

over welding, torchlight breaking

shadows on his face, hands cracked

into a parched map of fields he has woken –

the gods wanted us.

Think of their patient preparation:

the creature who left the rocking waves behind,

crawling up on some beach, the sun

suddenly becoming clear. Small thing

abandoning water for air, crooked body

not quite fit for either world, but the one

that finally made it. Think of all the others.

Much later, spine uncurls, jaw pulls back, brow-bone

recedes, and as day breaks over the dry plain

a rebellious boy takes an upright step

where primitive birds are shrieking above him.

He did it for nothing. He did it

against all odds. Bone of wrist, twist

of tooth, angel of atoms – an infinity

of courage sorted into fact

against the shining backdrop of the world.

The line of one man’s neck, bent –

torchlight breaking shadows on his face.

There was a creature who left the waves behind

and a naked child on a windy plain:

when the atom rips out into our only world

and we’re carried away on a wave of hot wind

I will love them no less: they are just how much

the gods wanted us.

Jane Mead (1958-2019)

. . . . . . .

The Geese

slicing this frozen sky know

where they are going –

and want to get there.

Their call, both strange

and familiar, calls

to the strange and familiar

heart, and the landscape

become the landscape

of being, which becomes

the bright silos and snowy

fields over which the nuanced

and muscular geese are calling.

Jane Mead (1958-2019)

. . . . . . .

To the Wren, No Difference

No Difference to the Jay

I came a long

way to believe

in the blue jay

and I did not cheat

anyone. I

came a long way –

through complexities

of bird-sound and calendar

to believe in nothing

before I believed

in the jay.

Jane Mead (1958-2019)

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

When Mike Barnett and I stopped at Newfound Gap (on US 441 smack in the middle of Great Smoky Mountains National Park) we were returning from the weekend lichens course at Tremont, part of the Southern Appalachian Naturalist Certification Program. We bow down in gratitude to John DiDiego, Education Director at Great Smoky Mountains Institute at Tremont, for convincing Dr. James Lendemer to teach this course. Dr. Lendemer is chief lichenologist at New York Botanical Gardens and literally wrote the book: Field Guide to the Lichens of Great Smoky Mountains National Park (which weighs 1.48 kg, not so much a “field guide” as an entire encyclopedia!).

Dr. Lendemer in his book names L. pulmonaria “Crown Jewel of America” – it is the biggest baddest lichen of them all. Thank you, James – we love lichens! Thank you GSMIT and SANCP and GSMNP. And thanks to all you little fungal hyphae, algal photobionts, cyanobacteria – you look mah-velous.

Resources:

More by and about Jane Mead at Poetry Foundation.

Field Guide to the Lichens of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Erin A. Tripp and James C. Lendemer, University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville, © 2020.

Great Smoky Mountains Institute at Tremont, Southern Appalachian Naturalist Certification Program.

. . . . . . .

[…] About/Submit […]